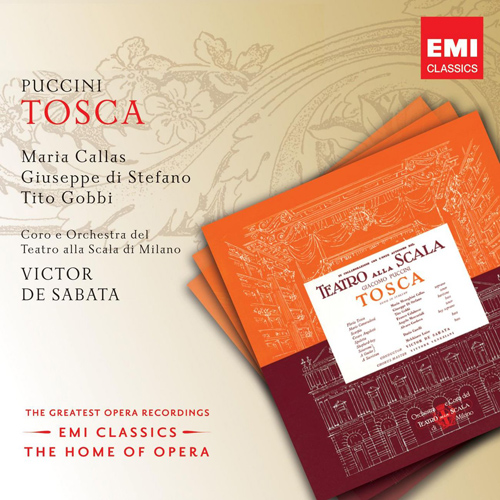

De Sabata conducts Puccini’s Tosca

Artist(s): De Sabata, Victor

Callas, Maria

Di Stefano, Giuseppe

Gobbi, Tito

Composer(s): Puccini, Giacomo

Series: EMI Great Recordings of the Century

My Opinion

Last week, one of the friends following my blog asked the question: “Jawad: how on earth someone who reviews legendary classical music recordings could possibly miss out on the great soprano Maria Callas?” In truth, this was not really a question, but rather a kind request in disguise. Before repairing this “injustice”, I would like to clarify two things that would hopefully absolve me: first of all, Dame Maria Callas (1923-1977) is not a great Soprano, she is the greatest of them all; and second, her spirit was actually present in my subconscious mind from my first post on, but like a culinary chef preparing his “plat de résistance”, I needed to serve appetizers first!

This landmark 1953 studio recording achieved classic status almost immediately after its release. The 1950s and 1960s were two miraculous decades for opera music making. And among all the artists in activity during these blessed times, legendary EMI producer Walter Legge in particular was instrumental in assembling incredible casts and orchestras for the likes of Furtwängler, Karajan, Klemperer, Giulini, Böhm and other prominent conductors of the time, who in turn created readings of Mozart, Verdi, Wagner, Puccini, and Strauss operas for the ages. The present recording is one of these glorious endeavors. Here La Divina shines of course through her vocal powers – she was then at her absolute peak, vocally speaking – but also thanks to her indelible dramatic characterization of Tosca, powerful charisma, and utterly captivating presence on stage. She is very well supported by a great cast, dominated by Tito Gobbi – probably the greatest Scarpia on record, and an astonishingly youthful and fresh Giuseppe di Stefano in the Cavaradossi role. Italian conductor Victor de Sabata, despite not enjoying the fame of a Toscanini or a Karajan, gives here a competent performance and directs a Milan La Scala Orchestra and Chorus that seemed predestined for the work. De Sabata’s relentless, almost obsessive, pursuit of perfection during the grueling recording sessions in August 1953, is abundantly documented by accounts from Gobbi and others, and could only be matched by Callas’ artistic perfection and Legge’s outstanding care and control of the technical details of the production. The mono sound of the recording, though not ideal, is pretty good for its time.

This is quite simply one of the top recordings of the 20th century, all genres considered! No true lover of classical music should miss it out, under any circumstance.

Reviews

“This set has been so unanimously regarded down the years as one of the all-time greats of the record catalogue that it is faintly embarrassing to have to write about it; surely everything that can be said has already been done so?

Well, one question that prospective buyers will wish to know is, can a transfer made, however musically and intelligently, with original LPs, match EMI’s own version(s) using the master-tapes, to which they retain their unique access? The answer is partly supplied in transfer engineer Mark Obert-Thorn’s brief note, which it is worth quoting fairly fully.

The original LPs featured pitch discrepancies between and even within sides. There were also bad edits and sudden, obtrusive volume fluctuations. On EMI’s three CD issues, some of these problems were corrected in one edition and then undone in the next, while other, new editing errors crept in …. The most recent GROC transfer compounded the problems by pitching the recording noticeably flat, an error which, in addition to adding nearly a minute and a half to the running time of this relatively brief opera, also affects the listener’s perception of tempo and vocal timbres.

For the present transfer, I assembled no fewer than ten LP copies of the set, and spent the greater part of eight weeks transferring, listening, comparing and re-doing the project until I was satisfied with the results”.

The question of pitch is obviously of considerable importance and my only query is that Obert-Thorn’s version may still be very fractionally low. I have no very sophisticated instruments to hand and base myself on the consideration that I know my domestic piano has slipped just slightly from the 440’ currently used in Italy to about 438’, and most recordings, including an Italian EMI LP pressing of extracts from this recording, sound just fractionally sharp of my piano. This recording sounds in tune with it!

However, this begs all sorts of questions. For one thing, LP turntables sometimes varied a little between each other, or even fluctuated slightly while playing. They also had a tendency to play a fraction faster when they got older, as the mechanism that clawed back the motor got old. I’m not for a moment suggesting that Obert-Thorn would use anything other than highly sophisticated and constantly checked equipment, but this might be the problem with mine, although I don’t normally notice a particular difference when I compare the same recording in LP and CD formats.

But another question is, did La Scala use 440’ back in 1953 or something slightly lower? Is c.438’ actually right? Did the EMI engineer who transferred the GROC version at a lower pitch still have historical evidence for doing so? Just to compound the mystery, the Garzanti Enciclopedia della Musica (in Italian) states that the 440’ standard was set at the Congress of London in 1939, well before this recording (but would Mussolini’s Italy of 1939 have paid heed?) while the Grove Concise Dictionary says it was decided by the International Organization for Standardisation in 1955, which would leave open the possibility that La Scala was still using something lower in 1953. I also note that the 1956 Cetra set under Basile, recorded in Turin, plays at the same pitch as Obert-Thorn’s transfer of the present set, suggesting that he is right and pitch in Italy did remain fractionally low in those years. As I happen to live in Milan I will try to make enquiries, but it’s amazing how some things can sink without trace.

Need the general listener care a hoot? Well, even the minute dichotomy between my LP and the CDs alters our perceptions; the CDs have a warmer, less strained sound, generally with a fine body to it and only minimal distortion at strenuous moments. The acoustics of La Scala were less sympathetic than those of Rome’s Santa Cecilia which Decca were using at the same period and that cannot be changed, but all things considered there seems no reason why anyone who doesn’t have this performance yet should pay more than Naxos’s rock-bottom price.

But what about the performance? It was a pace-setter in many ways. For one thing, Italian operas in those days were invariably recorded under the baton of an “Italian operatic conductor”, a soundly trained gentleman who knew the ins and outs of the repertoire, understood the human voice and was respected by singers because he “let them breathe” (which could be a synonym for “let them do what they liked”). I don’t want to knock the talents of such capable artists as Serafin, Votto, Erede, Molinari-Pradelli, Capuana, Basile, Previtali et al, or to suggest that they were all on an equal level, but it is odd that during Toscanini’s reign at La Scala HMV recorded a long series of operas there, but under Carlo Sabajno; another great conductor, Vittorio Gui, got to record a few operas thanks to his Glyndebourne associations, Antonio Guarnieri none at all. Victor De Sabata, in his only studio opera recording (a few live performances have turned up), was therefore the first Italian conductor recognised internationally as a “great conductor” to record Puccini in Italy (Toscanini’s late New York performance of “La Bohème” preceded this). After this came the Karajan/Callas “Butterfly” and the Beecham “Bohème” and the pendulum went too far the other way, leading to personalised interpretations by the likes of Sinopoli and Bernstein with the result that the work of the “Italian operatic conductor” needs reassessing for its enshrinement of a lost tradition.

De Sabata’s contribution to this “Tosca” cannot be overestimated, for the performance is totally integrated. After so many Callas sets where the diva shines, the others do what they can and the conductor follows along, here she is obviously happy to collaborate with an artist of her own stature. This is a “Tosca” of seething tension and menace (surpassed in my experience only by a short video extract under Mitropoulos) in which every note falls into place in the overall drama. Callas, who was still notable in 1953 for sheer vocal beauty as well as gut conviction, gives so much more than in, for example, the (too-) often re-released video of Act 2 from Covent Garden under the noisy, messy Carlo Felice Cillario, and Giuseppe Di Stefano, an inconsistent artist, gives of his very best as Cavaradossi. Tito Gobbi’s celebrated Scarpia is a non-pareil of slimy nastiness. Nobody else much matters in this opera, but they are all good, an unattractive shepherd apart.

In short, the mythical set lives up to its reputation and those who do not have it should set this to rights. The presentation is consistent with this series: good notes and detailed synopsis but no libretto, which you can get from Internet easily enough. Will Naxos and others please get it into their heads that “De” and “Di” in Italian names, unlike equivalent words in virtually every language, have capital letters because they are an integral part of the surname and you look up De Sabata and Di Stefano in the encyclopedia under “D” not “S”.” – Christopher Howell.

“Can Maria Callas bail out Mariah Carey? EMI apparently hopes so, as we have before us the third CD appearance of the famous soprano’s legendary Tosca, this time on the label’s Great Recordings of the Century imprint. So much ink has been spilled on this recording since its release in 1953 that little needs to be said about it here. Suffice to say that it has earned its status as the reference standard on disc, even if, as many have quibbled, you don’t get the ultimate in vocal beauty from Callas (turn to Tebaldi on Decca or Caballé on Philips for that). Nonetheless, this recording possesses the all-star cast with the ultimate Scarpia in Tito Gobbi and a sensitive Giuseppe di Stefano as Cavaradossi. Victor de Sabata, one of the better (but under-recorded) conductors of the 20th century, leads a thrilling, vital, and detailed performance.

At this point we must turn our attention to Allan Ramsay, the remastering engineer for this release and for the 1997 Callas Edition version. There is no question that this latest effort is a sonic improvement over the previous one, so if you are scratching your head at your local CD store over which one to buy (assuming, incredulously, that you do not already have this recording), don’t hesitate to grab the newer one.

Ramsay has tamed some of the stridency (compare just the opening chords), smoothed some of the more clumsy edits, and opened the soundstage significantly, an impressive achievement when you consider that this is still just a monaural (albeit fastidiously produced) recording. Skipping to the “Te Deum” section at the end of Act 1, the results of Ramsay’s work are really in evidence: Gobbi’s sinister but stentorian declamations (“Va, Tosca!”) over the organ and ever-growing orchestra and chorus are clearly delineated, vibrant, and full of presence. By contrast, in the same section of the 1997 edition the sound is flat, two-dimensional, distant, and muted.

The “new” Tosca also is a better value: you get a four-language libretto, expanded track indexing, and other goodies for Callas fans. Now all we have to do is wait for this great recording’s next revival on Mini-disc, DAT, DVD-Audio, Super Audio CD, and mp3–at which point perhaps Alain Levy, the new CEO of EMI, can crow to shareholders that the company will have recouped as much as one percent of Mariah Carey’s buyout.” – Review on ClassicsToday.