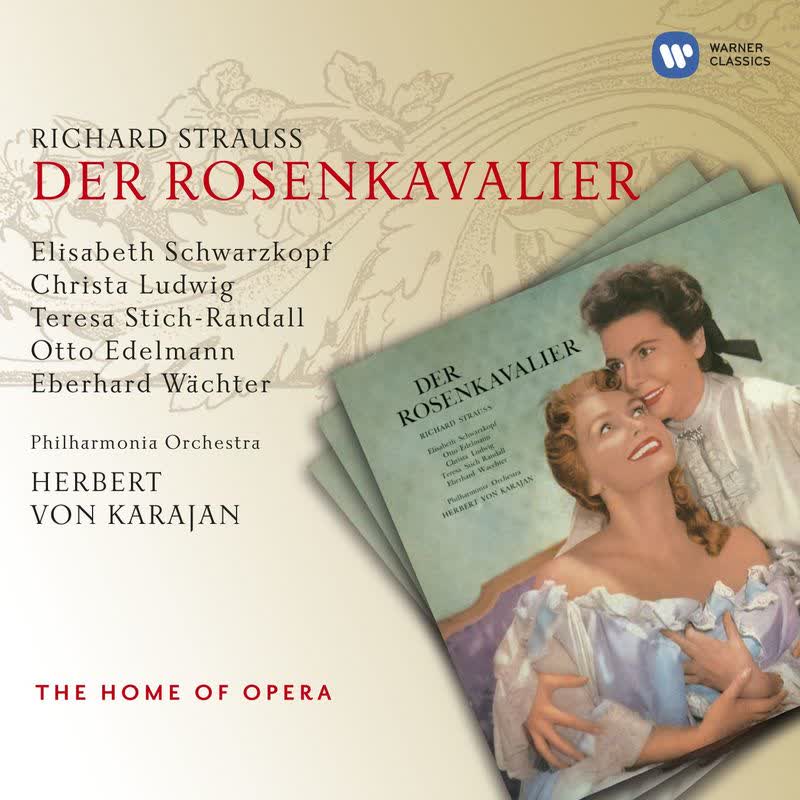

Karajan conducts Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier (EMI’s Great Recordings of the Century)

Artist(s): Karajan, Herbert von

Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth

Ludwig, Christa

Stich-Randall, Teresa

Edelmann, Otto

Composer(s): Strauss, Richard

Series: EMI’s Great Recordings of the Century

My Opinion

Is getting a reincarnation of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf in the realm of the possible? As with the likes of Maria Callas, Victoria de Los Angeles, or Christa Ludwig, I think not. For the great Austro-British soprano’s near-perfect endorsement of the operatic Viennese tradition has never been equaled. And this is particularly striking in the works of Mozart and Richard Strauss. This recording from the mid 1950s is a stunning case in point.

Legendary conductor Herbert von Karajan (1908 – 1989) does not need an introduction, of course. In the eye of the general public, he is the very incarnation of the virtuoso conductor. He could have his occasional quirks, especially in the last three decades of his admirable career. But in the 1950s, when this landmark recording of Strauss’ masterpiece was committed to disk, he was a genial conductor on all possible accounts. In this recording he directs a dream cast to accompany Dame Schwarzkopf, led by two magnificent duos of singers, Ludwig/Stich-Randall and Edelmann/Wächter. The Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus are at the peak of their powers.

The only competition to this marvelous recordings is the earlier classic set by German conductor Erich Kleiber. Both sets have their unique strengths and complement each other in many ways. As such they have their due place in your library.

Reviews

“Some while back I reviewed the classic 1954 Erich Kleiber Rosenkavalier, reissued on Decca’s “Legendary Performances” series (467 111-2). Now the 1956 Karajan is available as one of EMI’s Great Recordings of the Century.

The Kleiber was the first complete recording of the work. It also enshrines a deeply authentic approach, nurtured in Vienna under the likes of Clemens Krauss and Kleiber himself and a trio of ladies – Reining, Gueden and Jurinac – who had grown up with their parts in a Vienna where the composer himself was very much a living memory (and Gueden had taken up the part of Sophie at his request). As a recording it was a first, but as a performance it marked the end of a long line in which the work was presented with total understanding and sympathy rather than interpretation as such. The Karajan came only two years later, but by this time Strauss was, as it were, a public monument. The EMI set ushered in a new era of “personalised interpretations”.

What this means in practice can be heard in the Marschallin’s soliloquy on the passing of time. Schwarzkopf’s semi-whispered phrases amount to a deeply imaginative approach on the part of both her and the conductor, and with the distant clock striking the music comes to a complete standstill. Schwarzkopf’s final phrase is preceded by a pause and is then as long-drawn-out is it could possibly be. Reining and Kleiber, by contrast, give us Strauss “neat”. Abetted by a brighter, more forward recording they could seem rough-mannered as they keep things on the move (no indulgence as the clocks strike), except that they give us one essential ingredient that Strauss, in love with the soprano voice right through his career, must surely have longed for; the almost sensual satisfaction of a full-toned voice billowing and soaring across the footlights. That is what people go to the opera for, and Schwarzkopf and Karajan seem intent on withholding this. Invariably, when she enters or returns to the scene, she does so not like a prima donna whose task is to hold the stage, but emerges imperceptibly from the orchestra. As so often, Karajan’s sheer refinement seems to cushion the listener from the full impact of the music. Similarly, as love dawns between Octavian and Sophie, Teresa Stich-Randall’s high pianissimo Bs and Cs have a pure, disembodied quality which exhibits a control unmatched by Hilde Gueden, who nevertheless has the essential oomph-factor. Best of all, maybe, was Schwarzkopf herself back in 1947 as a free-soaring Sophie in a short extract recorded with a more unconstrained Karajan.

Considering all the moments of stasis, it is remarkable that Karajan’s overall timings are faster in all three acts. In certain moments, such as the pantomime at the beginning of Act 3, he really goes like the wind, and with Kleiber you feel the singers have that spot more time to express their words in the comic exchanges. Still, this was only the first of the personalised Rosenkavaliers, and Karajan was always a great master of the overall line, something which later purveyors of faster-than-fast alternating slower-than-slow rather lost sight of. All this would nevertheless seem to point to a recommendation for Kleiber, even taking into account Edelmann’s less boorish Ochs, real luxury casting of the smaller roles (Gedda is wonderful as the Italian tenor, where Anton Dermota struggles a bit) and a more refined if a little recessed recording.

Except that, come the Act 3 trio, the overwhelming climax of the work, and Karajan finally loses himself in the music, and when this happens all his refinements fall into place. At last the voices are encouraged to soar out freely (had he been saving up for this all along?) and even Kleiber’s glorious account is quite surpassed. This at least is one of the “Great Recordings of the Century”. I don’t know if this in itself adds up to a recommendation ahead of Kleiber, but it does rather sound as if you’ll need both of them.” – Christopher Howell, review for musicweb-international.com.