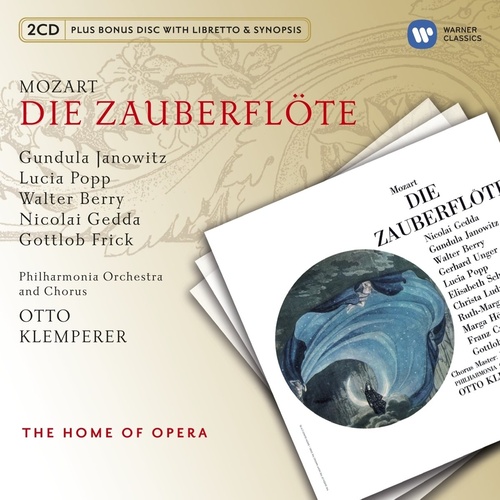

Klemperer conducts Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte

Artist(s): Klemperer, Otto

Gedda, Nicolai

Janowitz, Gundula

Berry, Walter

Popp, Lucia

Frick, Gottlob

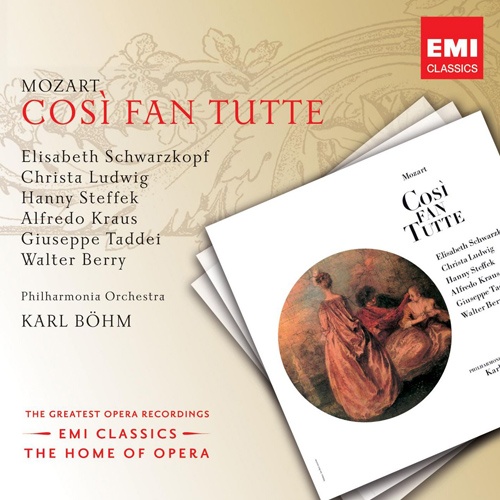

Schwarzkopf, Elizabeth

Ludwig, Christa

Composer(s): Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus

Series: EMI Great Recordings of the Century

My Opinion

I could not delay the presentation of this jewel anymore. Here is one of the greatest recordings of Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte. The work has special meaning to me, being the first complete opera I listened to from first to last note in a single session!

Die Zauberflöte is Mozart’s last completed opera – he completed it about three months before his death – and arguably one of his greatest artistic creations. In many respects, it embodies the culmination of the operatic art of the great Austrian genius. The present recording by the illustrious German conductor Otto Klemperer (who was 79 at the time of the recording!) has never been out of the catalog since 1964. The cast assembled by producer Walter Legge is peerless and would be inconceivable nowadays, as it featured a young Nicolai Gedda playing Tamino, Gundula Janowitz as Pamina, an incomparable trio of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Christa Ludwig and Marga Höffgen playing the Three Ladies, an astonishing Sarastro in Gottlob Frick, and finally a glorious Queen of the Night in Lucia Popp. The latter truly stands out, and her marvelous interpretations of ‘O zittre nicht, mein lieber Sohn!’ and ‘Der Hölle Rache….’ never fail to move the hardest hearts. This constellation of artists is beautifully directed by a rejuvenated Klemperer, with a decidedly romantic approach to the score.

In my opinion, only three other modern – post 1950 – performances come close to match the artistry of Klemperer’s account: Herbert von Karajan’s celebrated 1950 recording with the Wiener Philharmoniker, Karl Böhm with the Berliner Philharmoniker, and Ferenc Fricsay 1953 recording with RIAS Symphonie-Orchester Berlin. I promise to present these three recordings in the future. In the meantime, enjoy Master Klemperer and his folks!

Reviews

“Otto Klemperer’s 1964 recording of the Magic Flute has always been a magical performance of a work Klemperer was somewhat in awe of. Like its two predecessors on EMI – Beecham’s 1938 performance with the Berlin Philharmonic and Karajan’s with the Vienna Philharmonic in 1950 – the conception is laid out on the grandest of scales. There is no dialogue and a broadening of tempi where others, particularly period performers, take the work more fluidly. In other words, it is almost anathema to modern day tastes.

Incomplete and old-fashioned it may be, but this performance stands head and shoulders above virtually all others. In part this is due to the singing, which is superlative. Walter Legge had boasted that the cast would be near perfect. In casting Schwarzkopf, Ludwig and Höffgen as the Three Ladies – luxury casting it would be impossible to achieve today – he did indeed create a performance that is vocally unrivalled, underpinned as it is by the unmatched Sarastro of Gottlob Frick and the glorious Queen of the Night of Lucia Popp.

From the very opening of the Overture, with divided violins etching their notes like angels, this is first and foremost a classically poised performance. There is weight of tone, but it is balanced by a natural lightness of touch. Klemperer’s great gift in this opera is his ability to unify the contrasting elements of Mozart’s scoring whether it be in the exalted seria in the Sarastro and Queen of the Night arias, or the pantomime buffoonery of Papageno’s arias. Klemperer, often the most high-minded of conductors, is here a master of the burlesque.

There is so much glorious singing in this recording it is difficult to point out singular highlights for the whole performance is one unending highlight. Lucia Popp’s singing of ‘Der Hölle Rache….’ is an obvious choice the high, murderous tessitura writing holding no fears for a voice which was then young and at its most ecstatic. The Papagena and Papageno duet, near the opera’s close, has Ruth-Margret Pütz and Walter Berry knocking spots off each other with the fleetest woodwind and strings joining in the fun. Gottlob Frick achieves near impossibly low notes in his Isis and Osiris aria.

The Philharmonia (at a difficult time for the orchestra) are sublime to a man, with Gareth Morris’ flute perhaps taking the winner’s prize for most characterful playing. Klemperer himself was surely more vibrant than in any other recording he made in studio post-war.

The stereo recording was always a success, with the balance between voices and orchestra more natural than in some other issues from the time (Giulini’s Verdi Requiem, for example). EMI’s remastering is well focused, if a little dry, and there is some distortion in the choral section that ends the opera. There is, however, more ambience than in previous issues of this recording on CD and at mid-price cannot be missed.

Unlike some of EMI’s recordings in this series this is truly a Great Recording of the Century.” – Marc Bridle.

“As with Karajan and Böhm’s first recorded Magic Flutes, and the pioneering Beecham set, Klemperer’s 1964 EMI version includes the arias and ensembles only, omitting the dialogue. Klemperer’s mesmerizing concentration compensates for the loss in dramatic immediacy. He patiently unravels Mozart’s scoring like a veteran storyteller who relishes every little detail of plot and subplot. The pacing is weighty at times, but never ponderous in the manner of Klemperer’s later Mozart opera recordings.

There’s not a weak link in the cast. The stratospheric reaches of the Queen of the Night’s two arias hold no problems for Lucia Popp, although she is not the natural coloratura Roberta Peters is for Böhm (DG), or Wilma Lipp for both Karajan and Böhm’s mono traversals. Nicolai Gedda brings ardency, tenderness, and intelligence to Tamino, and Walter Berry’s rounded, splendidly articulated Papageno is a joy. Gottlob Frick takes easy charge of Sarastro’s low-lying tessitura (quite impressive for a 58-year-old singer), while the young Gundula Janowitz’s fresh, radiant timbre is just right for Pamina. EMI’s remastering enlivens the bloom and sparkle that characterizes this classic recording. To experience Mozart’s valedictory opera in its true theatrical context, however, Böhm’s Vienna recording for DG (with Solti’s Decca remake as a close second) remains your basic Zauberflöte.” – Jed Distler.